[click an item below to go to other documents]

| Previous document: --none-- | List of documents | Next document: --none-- |

| Table of Contents for this Volume | ||

| Cover page with links to All Volumes (1 to 4) | ||

Anne Catherine Emmerich was a German peasant woman who bore the stigmatic wounds of the Passion of Christ on her hands, feet and side, as well as the bleeding Crown of Thorns on her head. She was told by Our Lord that her gift of seeing the past, present and future in mystic vision was greater than that possessed by anyone else in history. Born in Flamske in Westphalia, Germany, on September 8,1774, she became a nun of the Augustinian Order at Dulmen. She had the use of reason from her birth and could understand liturgical Latin from her first time at Mass. During the last 12 years of her life, she ate no food except Holy Communion, nor took any drink except water, subsisting entirely on the Holy Eucharist. From 1802 until her death in 1824, she bore the wounds of the Crown of Thorns and from 1812, the full stigmata of Our Lord, including a cross over her heart and the wound from the lance.

During the last five years of Sister Emmerich's life, the day-by-day transcription of her visions and mystical experiences was recorded by Clemens Brentano, poet, literary leader, and friend of Goethe and Görres, who, from the time he met her, abandoned his distinguished career and devoted the rest of his life to this work. The immense mass of notes preserved in his journals forms one of the most extensive case histories of a mystic ever kept and provides the source for the material found in this book, plus much of what is found in her two-volume definitive biography written by V. Rev. Carl E. Schmöger, C.SS.R.

The decree affirming that Anne Catherine Emmerich had lived a life of heroic virtue was promulgated at the Vatican on April 24, 2001.

The Life Of Jesus Christ And Biblical Revelations is one of the most extraordinary books ever to be published. These four volumes record the visions of the famous 19th-century Catholic mystic, Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich, a nun who was privileged to behold innumerable events of biblical times, going back all the way to the creation of the world. She witnessed the fall of the Angels, the sin of Adam, Noe and the Flood, the building of the Tower of Babel, the Old Testament Patriarchs, the life and beheading of St. John the Baptist, the life of St. Anne, St. Joseph, the Blessed Virgin Mary, St. Mary Magdalen—and of course the birth, life, public ministry, Crucifixion and Resurrection of Jesus Christ, as well as the founding of His Church. And besides describing persons, places, events and traditions in intimate detail, Anne Catherine Emmerich also sets forth the mystical significance of these visible realities, for their hidden spiritual meanings were to her an open book.

A work that for over a century has made converts, caused vocations to the religious life, and inspired thousands of people to a profounder love of their Faith, The Life of Jesus Christ and Biblical Revelations is only now beginning to receive the circulation that it so richly deserves. St. John the Apostle declares at the end of his Gospel that if all the deeds of Jesus Christ were recorded, he thinks the world itself would not be able to hold the books that would have to be written. (John 21:25). Through the remarkable visions which God granted to Anne Catherine Emmerich, people of today are allowed to witness some of these profound and stirring events. These revelations constitute one of the greatest treasures of Catholic mystical writing. One is even forced to conclude that they are a special gift of Divine Providence—an extraordinary favor granted by God to this confused and unbelieving age.

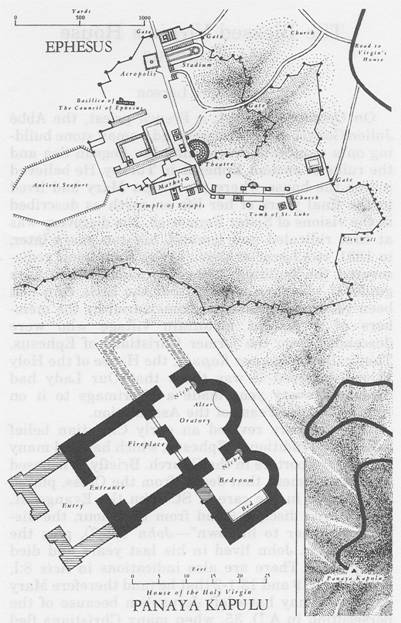

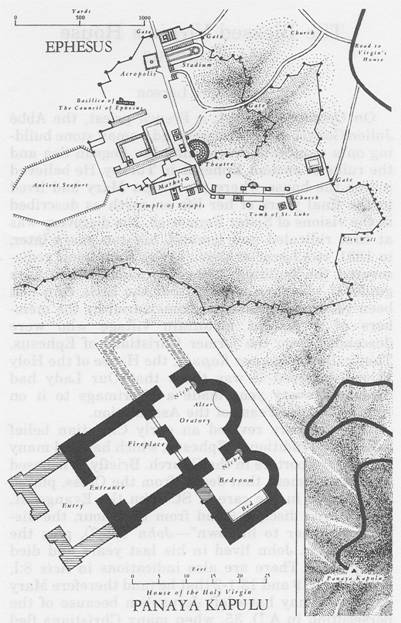

On October 18, 1881, a French priest, the Abbé Julien Gouyet of Paris, discovered a small stone building on a mountain overlooking the Aegean Sea and the ruins of ancient Ephesus in Turkey. He believed it was the house where the Virgin Mary had lived in the final years of her life on earth as described in the visions of Sister Emmerich. His discovery was at first ridiculed and ignored, but ten years later, in 1891, two Lazarist missionaries from Izmir rediscovered the building, using the same source as a guide. It was then learned that the little ruin had been venerated from time immemorial by the members of a distant mountain village who were descended from the former Christians of Ephesus. They called it Panaya Kapulu, the House of the Holy Virgin, believed it was there that Our Lady had died, and every year made a pilgrimage to it on August 15, the Feast of the Assumption.

The discovery revived an early Christian belief called the Tradition of Ephesus, which has had many learned supporters in the Church. Briefly, it is based on the statement that Jesus, from the Cross, placed His Mother in the care of St. John the Evangelist, His beloved disciple ("and from that hour, the disciple took her to his own"—John 19:27), plus the fact that St. John lived in his last years and died at Ephesus. There are also indications in Acts 8:1, 9:26-30,11:19 and 12:1-2 that he (and therefore Mary with him) may have left Jerusalem because of the persecution in A.D. 35, when many Christians fled

from the Holy City and the Holy Land. These texts also show that he was not there for the next fourteen years, during which time it may be presumed that Mary was still alive.

Ephesus also is the site of the ancient Church of St. Mary, one of the oldest churches in the world dedicated to the Virgin. It was built in the time of the Emperor Constantine, about A.D. 330, when Christians were first permitted to worship publicly in the Roman empire. At this time it was unusual—and some scholars think not permitted—for churches to be named in honor of saints except in places made sacred by their residence or deaths.

The Tradition of Ephesus is referred to in the writings of St. Epiphanius of Salamis (A.D. 315-403) and, as such, is the oldest known early Christian belief of which there is record concerning Our Lady's last earthly home. In spite of its antiquity, however, it remained little known, and in time was almost completely eclipsed by another more popular, though later, belief, i.e., that Jerusalem was the site of the Blessed Virgin's death and Assumption. The Tradition of Ephesus was never completely forgotten, however. In the seventeenth century the eminent church historian, Tillemont, adopted it; and in the eighteenth century the learned Pope Benedict XIV (pontificate 1740-1758) wrote in a treatise on Christ's Last Words from the Cross that "St. John, departing for Ephesus, took Mary with him, and it was there that the Blessed Mother took her flight to Heaven."

Following the discovery of the House of the Virgin, Pope Leo XIII blessed the first international pilgrimage to it, and in 1896 discontinued indulgences formerly attached to the "Tomb of the Virgin" at Jerusalem. His successor, St. Pius X, greatly encouraged devotion to the shrine. And in 1951 Pope Pius XII, the pope who defined the dogma of the Blessed Virgin Mary's Assumption into Heaven, removed a text from the Breviary which referred to the tradition of Jerusalem. He also elevated the Tomb of St. John, the Church of St. Mary and the House of the Virgin to the status of Holy Places, a privilege later made permanent by Pope John XXIII—thus making of Ephesus, as it were, a new Holy City for the modern world.

By that time interest in the House of the Virgin had been aroused to such an extent that a road was built up to it and the isolated ruin on the mountain was restored. Since then it has been visited by increasing numbers of pilgrims from all over the world, including Pope Paul VI, who was there on July 26, 1967, and Pope John Paul II, who visited it on November 30, 1979.

[click an item below to go to other documents]

| Previous document: --none-- | List of documents | Next document: --none-- |

| Table of Contents for this Volume | ||

| Cover page with links to All Volumes (1 to 4) | ||